Megan Basham: My Response To JD Greear

As JD Greear is the first major figure in my book to publicly object to my depiction of his statements and actions over the last few years, I’ll deal with his objections one by one.

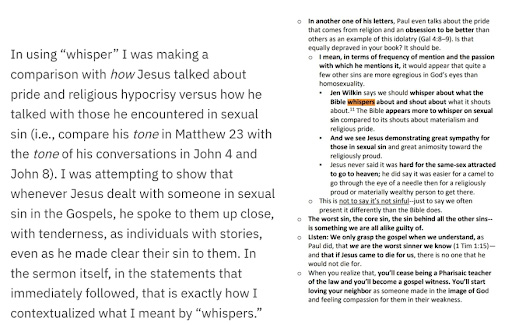

1) Greear feels it was not fair to mention his sermon wherein he said the Bible whispers about sexual sin because he later released a statement reversing his position after two years of pushback.

But the fact that he did later say that he does not believe that the Bible only whispers about sexual sin is something I myself noted in the paragraph he quotes. Where then is our disagreement?

He says he was only speaking about Jesus’ “tone.” But the transcript of the sermon he links to shows this is not true. He was very clear that he was saying that the Bible whispers about the sexual sin itself, there is no contrasting of tone.

Further, the full context of the passage in my book shows that I was not accusing Greear of reversing his position on homosexuality but reversing his position on whether one should whisper about it as a sin. I stressed that it is important for the church not to whisper about this issue because the culture is not whispering about it. Indeed, there are few issues about which the culture speaks more loudly. As left-wing funded activists are being trained to come into conservative churches to try and change their doctrines on sexuality, it is all the more important that pastors not whisper. It is only through clarity and forthrightness that they can protect their sheep from such false doctrine. So it is not necessary for Greear to insist he still believes homosexuality is a sin. No one has accused him otherwise. Here are the two pages in question.

That said, I did not choose the major figures I feature in the book for an ill-advised comment or two but for patterns of behavior. And Greear, as has been ably demonstrated by Dr. Robert Gagnon, has a history of minimizing the seriousness of this culturally unpopular sin.

Meg Basham (@megbasham), in her new book Shepherds for Sale, was right to be critical of the views on sexuality and homosexuality presented by Rev. J. D. Greear, who is Neil Shenvi’s (@NeilShenvi) pastor (note: Neil has attempted to take Meg to task over her statements about…

— Robert A. J. Gagnon (@RobertAJGagnon1) August 6, 2024

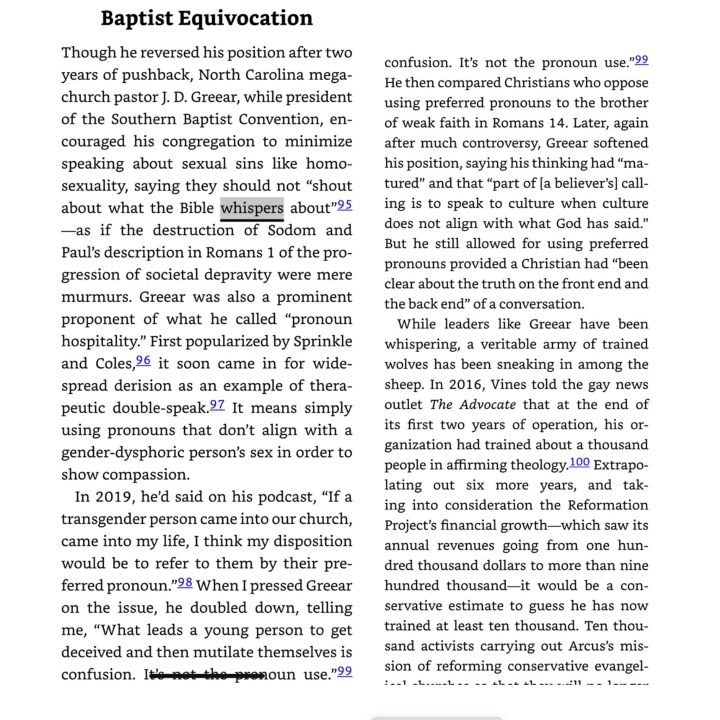

2a) Greear says he did not heavily push to change the name of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Greear’s own objections undercut his claim that he did not make a heavy push to change the name during his time as president. (Simply because others moved to allow alternative names does nothing to prove or disprove whether he did.) And as he concedes, he made the theme of the 2021 Convention “We Are Great Commission Baptists” and announced that his church would begin using that descriptor. That alone would be enough to support describing his push as “heavy.”

Additionally, in interviews with national newspapers like The Washington Post, Greear indicated his desire to see the denomination’s name change. (The fact that a reviewer of my book, Samuel James, also overlooked media interviews Greear gave during his time as SBC president does nothing to bolster Greear’s argument).

If the Washington Post misrepresented Greear in their 2020 interview, why did he not raise the issue then?

2b) Greear says retiring the gavel that had belonged to Robert E. Lee’s chaplain, John Broadus, was his right and does not make him a “progressive or a sellout.”

Of course, I did not write that retiring the gavel made him such. But his decision to retire the gavel (though Broadus had repudiated slavery and, in stark contrast to what we so often see from modern megachurch pastors, faced the ire of his dominant culture when he rebuked Southerners for their continued racism) illustrated Greear’s efforts to keep pace with the prevailing cultural preoccupations in the summer of 2020.

(We are not really to believe the timing of his decision, as Black Lives Matter activists were marching through cities all over the country, was coincidental, are we? As news reports noted at the time, his announcement about the gavel came a day after he gave an address calling on Southern Baptists to use the slogan, “black lives matter.”)

He now says he was primarily motivated by a desire to use the Judson and Armstrong gavels. But at the time, multiple news organizations were clear that Greear’s decision to retire the gavel was part of a broader effort to remove Confederate statues and icons from public display.

Again, if his motives were being misconstrued, even by The Gospel Coalition where he serves as a council member, why did he not correct the record then?

2c) Greear objects to my saying that the media fawned over him an antiracist reformer.

Greear says he could not find PBS, Washington Post, or “any other credible outlet” using this term for him. These were my words, which is why I did not put the term in quotes. But that the media fawned over him because of his bolstering of antiracist terminology like and priorities is clear.

I also chose the term because Greear himself used it and amplified it.

2d) Greear complains that I bring in larger cultural context like the removal of statues and the renaming of schools while discussing his activities.

Obviously, this is important to show how his preoccupations paralleled those that were dominating academic, entertainment, and corporate culture at the time.

As to his objection that he does not wear Patagonia vests, I said “megachurch pastors of Greear’s variety” favor that type of outdoor apparel. If he does not personally buy that brand, I can only say that he certainly wears vests that are Patagonia-like, and authors should be allowed some incidental creative license to make the reading more enjoyable.

2e) Greear complains that he has not used the lingo of CRT and antiracism.

What he does not mention is that I gave a specific instance where he did so. In a roundtable on racism Greear used the Aspen Institute’s glossary on “Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Racial Equity.”

You can see that video here.

Greear complains that he has not used the lingo of CRT and antiracism. What he does not mention is that I gave a specific instance where he did so. In a roundtable on racism Greear used the Aspen Institute’s glossary on “Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Racial Equity.”… pic.twitter.com/lNq3x9svr8

— Megan Basham (@megbasham) August 13, 2024

He also says in his response that he doesn’t use words like ‘hegemony; and isn’t even sure how to pronounce it. But he used it here:

So yes, Greear was employing CRT terminology in his pastoral role and in his role as president of the SBC .

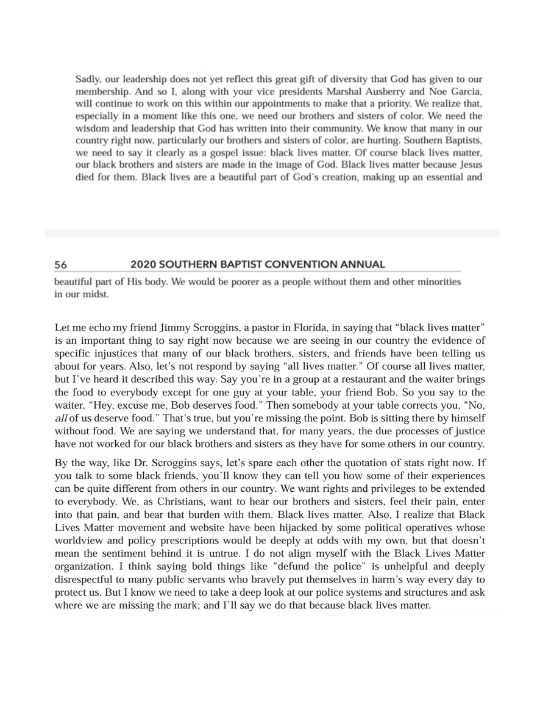

2f) Greear objects to my saying writing that he made supporting the Black Lives Matter movement a “Gospel issue,”and that he “explicitly distanced [him]self from the BLM movement even as [he] said Christians could affirm the three words.”

This does not quite go to what Greear said. In fact, what Greear said was that he “realizes that the Black Lives Matter movement and website have been hijacked by some political operatives whose worldview and policy prescriptions would be deeply at odds with my own.” [emphasis mine]. In fact, the BLM movement was Marxist from its inception. The divisiveness it created between categories it branded as the oppressed and the oppressors was always its aim, as has been well documented. Further, his insistence that American Christians need to “take deep look at our police systems and structures” was perfectly of a piece with the message of both the BLM organization and movement, even if he rejected their calls to defund the police.

Nowhere did Greear, as he claims, make it clear that he did not align himself with the BLM movement or its official goals. He indicated that he aligned with non-hijacked aspects of the movement. And one of its official goals was restructuring the policing system, which he explicitly said he did align with.

3) Greear objects to my pointing out that he set racial quotas for committee appointees because he says this was in line with past SBC resolutions and thinking.

All the resolutions he cites call for a general encouraging of nominations and appointees from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. None call for a racial quota.

Greear links to other SBC leaders touting the percentage breakdowns of their minority appointments. I don’t see this as a refutation of Greear’s DEI priorities, but rather further evidence that this is an issue worth spotlighting. But one book cannot contain every person involved in such activities and must be limited to the most recent and most prominent.

Greaar says his commitment to ensuring that two-thirds of his appointees were female or minorities is not a quota. Of course it is. His insistence that setting a requirement for a certain number of hires in a particular demographic isn’t an argument with me, it is an argument with the dictionary.

Greear then disagrees that it is ethnic Gnosticism for him to say that the SBC needs a quota of minority appointees because we need their special wisdom. On that, he’s free to take that position. But, as I wrote in my book, I see Greear’s belief that female and minority appointees will have a particular wisdom that male and white appointees will not as a perfect example of the phenomenon Voddie Baucham wrote about when he described the coined the term ethnic Gnosticism—the belief that minority Christians possess some special insight available only to them by virtue of their color.

4) Greear says that the paragraph in my introduction reads like his words came from one sermon.

I disagree and I’m not sure why he would think so. The fact that I wrote “Greear went on to liken” suggests a second sermon. I also include two different citations to the two different sermons. How then could it not be clear I was speaking of two different occasions?

To my asking about evidence of Greear’s claim that “closet racists and neo-Confederates” are in SBC churches, Greear offers this: “Many friends I had in seminary could recount a time they heard a racist joke offered by someone in their church.”

Racist jokes are bad, to be sure. But they would not seem to rise to the level of a term like “neo-confederate.” As to the jokes, Greear graduated from seminary in 2003. So his motivation for warning of “closet racists and neo-Confederates” in SBC churches in 2021 was hearing from friends more than 20 years before that they once heard a bigoted joke?

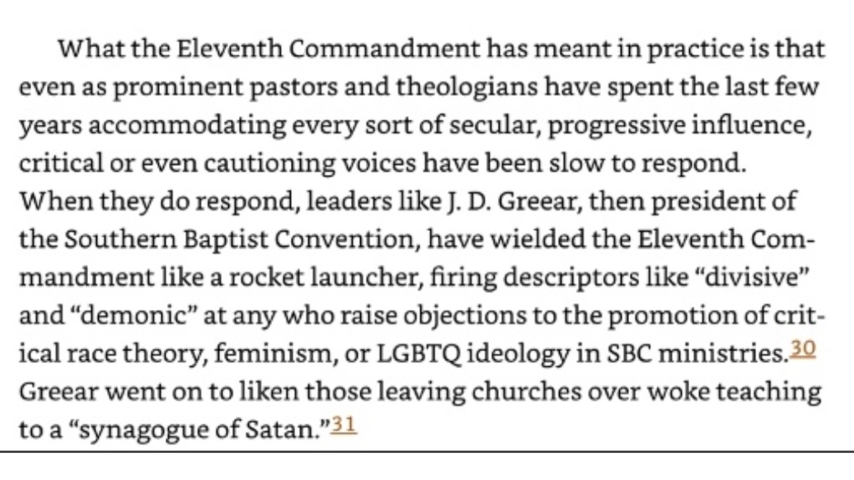

Greear says that when he used terms like “divisive” and “demonic” he was not “refer[ing] to people who ‘raised objections’ at all, but rather those who deliberately stirred up division.”

But Greear does not distinguish how observers could differentiate between those who had legitimate criticism of him and those who were simply stirring up division. Nor did he indicate that any of the critiques levied against him were legitimate.

This rhetorical approach allows the hearer to class any criticism among the division stirrers. And this is how his comments were widely received at the time, as indicated by essays like those from Pastor Gabe.

5) Greear points out that many SBC leaders besides him were involved with the secular-left funded Evangelical Immigration Table.

True enough, and that is why I make that very point at several points throughout the immigration chapter.

Greear says he was not speaking of Trump’s general border policies as wicked but only his family separation policy. To be fair, I could have been more specific in that sentence about which Trump border policy he was objecting to. That said, only a couple of sentences later I reference “Greear’s ire toward Trump’s six-week-long policy of family separation.”

So I do indicate to the reader in the same paragraph precisely which policy Greear was addressing.

Greear then says he did not speak out on the Biden Administration rejecting Cuban refugees because he had completed his term as SBC president and had “unplugged.” He says he was on vacation with his family.

Fair enough if Greear no longer wanted to comment on immigration policy. But the issue of the Biden Administration denying asylum to Cuban refugees (who tend to be conservative) while allowing millions of illegals from countries where persecution is not occurring was a part of the news cycle for more than two years. Presumably Greear was not on vacation the entire time.

And the fact remains that while Greear was critical of the Trump Administration’s immigration policies he was never likewise critical of the Biden Administration’s policies. I believe it was fair, as I did in the book, to ask why.

6) It is not to Greear’s credit that shortest section of his objection deals with the now-acknowledged wrong he committed against the former members of First Baptist Church-Naples by publicly branding them racists without any evidence that this was actually what they were.

Greear says: “When duly elected church leaders published an open letter to the SBC saying that some of those who had voted against the candidate ‘did so based on racial prejudices,’ I accepted their account and supported their public statement in good faith.”

No. One cannot in good faith publicly label ordinary members of a church racists without clear evidence.

Greear was SBC president at the time and had the biggest megaphone in the denomination. He had all the more responsibility not to speak unless he knew that the allegations were true.

An 80 year old woman who was pushed out of the church she had been a member of for 30 years cried on the phone to me. “When the church calls you racist, people believe it,” she said.

People were humiliated and ostracized and named the worst thing one can be called in our society. I would hope Greear would now do more than issue a tepid, “If anyone was falsely accused, I’m sorry I contributed to that.”

In summary, with the exception of whether comments Greear made came from a February or June 2021 sermon (and I will check this and correct if necessary), nothing Greear brought forth is an error.

Greear objects to my taking his words and his pattern of behavior seriously and setting it into the broader cultural context that he seems, quite obviously, to have been responding to.

There is nothing dishonest about this. It is, in fact, dishonest to suggest that this is an illegitimate or unusual form of journalistic analysis.